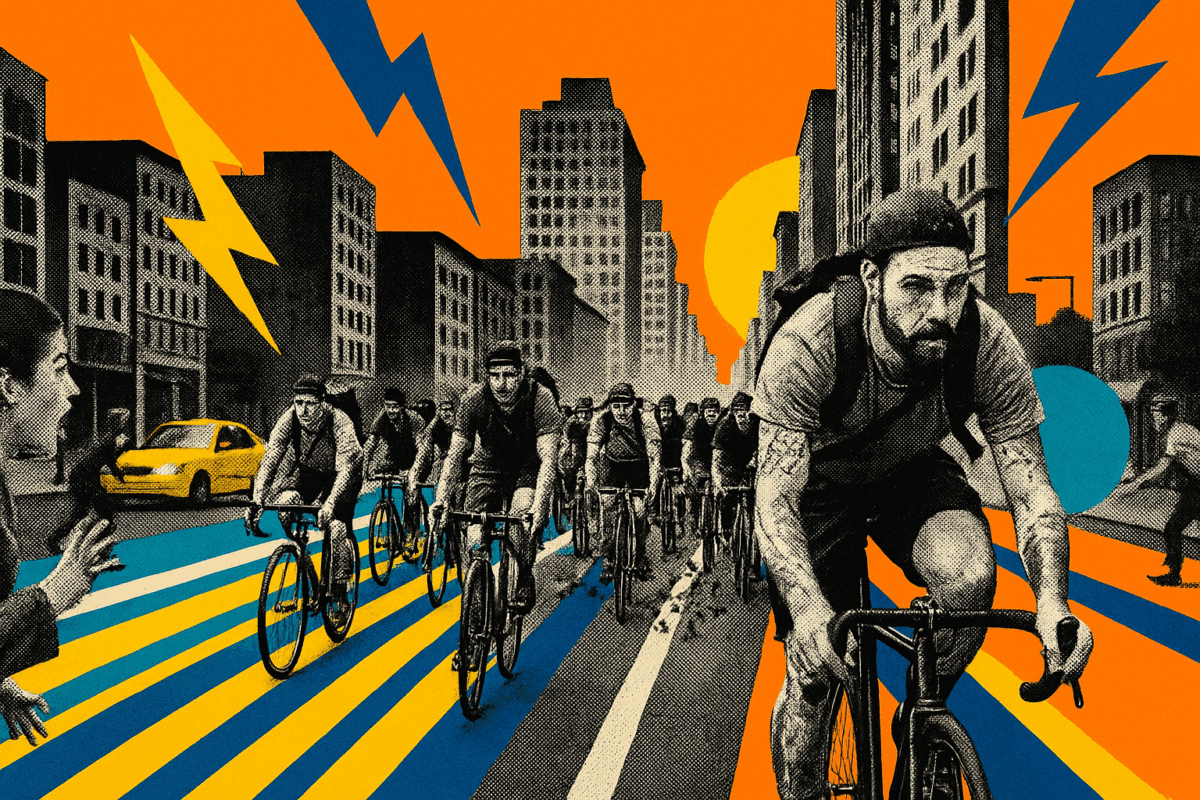

Ok, so you’re hauling ass through city traffic at 1 AM, checking a crumpled manifest, trying to figure out the fastest route to hit checkpoints scattered across town before everyone else gets to the bar. 🚴💡 No permits, no course marshals, no insurance—just you, your bike, and the city streets.

Welcome to alley cat racing, where bike messengers turned their daily grind into an underground competition that’s equal parts puzzle and adrenaline rush. This is organized chaos that’s been thriving in cities worldwide since 1989.

TL;DR:

- Alley cat races are unsanctioned checkpoint-based bike races that mimic messenger work—no set route, just addresses scattered across the city

- The first official race happened in Toronto on October 30, 1989, spreading globally after messengers shared stories at the 1993 Berlin courier championship

- Entry fees typically run $5 or free, with prizes ranging from custom bags to cash (one Toronto race awarded $3,000 CAD), plus the coveted DFL (Dead Fucking Last) prize

- These events exist in a legal gray area—organizers put responsibility on individual riders — crashes, arrests, and death as happened

A video titled “🔥 Hotline Cooper Ray | fixedgear” from the Terry B YouTube channel.

The origin story: Started by stoned teenagers, not messengers

Here’s what Wikipedia won’t tell you about how alley cats actually started.

John Englar founded the first race in Toronto, but it wasn’t some noble messenger tradition at first. As he told SLUG Magazine:

“Originally, it was a bunch of us who hung out in a warehouse, and we were like a bike gang. We were 17, 18, and we would get super-fucking stoned and we’d ride around the city terrorizing alleyways and riding the architecture.”

The name “alleycat” came from them literally being alley cats—jumping off stuff, riding through alleys, causing chaos. Messengers adopted the format later because it perfectly simulated their work: multiple deliveries, time pressure, navigating through traffic with zero set route.

Fun fact

The term “alleycat” refers to the races being “as unpredictable and fast-paced as a cat darting through an alley”—originally describing the punk teenage founders who terrorized Toronto alleys, not the messengers who later popularized them.

When Toronto messengers brought videos to the 1993 Cycle Messenger World Championships in Berlin, the concept exploded globally. Now you’ll find regular races everywhere from New York to Tokyo to Berlin—anywhere with a bike messenger scene or fixed gear culture.

The expansion through messenger networks was organic; no corporate sponsors, no official sanctioning bodies, just word-of-mouth through the tightly-knit courier community.

How alley cat racing actually works

It’s like the Amazing Race meets bike messenger work, but with beer at the finish line.

The manifest: Your mission briefing

The manifest is your race sheet—a paper clue sheet listing checkpoint addresses or cryptic directions. Organizers hand these out either 5-30 minutes before the start (giving you time to plan routes) or sequentially at each checkpoint (more chaotic, mimicking actual messenger dispatches).

Your job? Hit every checkpoint, get proof you were there, then haul ass to the finish before anyone else. The route between stops is entirely up to you. Take the bike lane? Cut through the park? Wrong-way down a one-way? That’s your call (and your legal liability).

This format tests city knowledge as much as raw speed. A slower rider who knows the back alley shortcuts can beat someone faster who takes the obvious route. It’s why messengers dominated early races—they’d spent years learning every shortcut, one-way exception, and traffic pattern.

Checkpoint chaos

Checkpoints come in different flavors designed to test navigation, bike skills, and sometimes your stomach:

Manned checkpoints have volunteers with stamps or pens who mark your manifest. Unmanned checkpoints require you to answer questions about landmarks—like “Name the politician referenced on the statue at 34th & Vine.” These prove you actually visited the spot rather than just looking it up.

Many races include task checkpoints where you’ve got to complete challenges before getting your next location:

- Take a shot of hot sauce or whiskey

- Perform fixed gear tricks or skid stops

- Climb a specific number of stairs

- Get makeup applied by volunteers

- Sing karaoke at a gay bar (yes, really)

- Recite messenger trivia

- Write haikus or fold origami for themed races

Creative tasks from real races:

- Sumo wrestling in diapers with thumb wrestling to determine winner (Japanese-themed race)

- Getting slapped with bloody panties (someone’s least favorite)

- Stealing matchbooks from bars before they run out

- Riding your bike through a 27″ wheel rim without touching it

- Drawing on yourself with makeup at sequential checkpoints, arriving at finish looking like a clown

One organizer explained: “The tasks let us be as creative as we desire.” The creativity is the point—organizers use these challenges to inject personality and make fast navigation meaningless if you can’t handle a bike trick or a shot of tequila.

Some racers skip tasks entirely, taking the point penalty to save time.

Race formats: Three ways to suffer

| Format | How It Works | Strategy Level | Time to Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential | First checkpoint given at start; next revealed upon arrival | Low – just ride fast | None |

| Checkpoints Up Front | All locations given 5-30 min before start | High – route planning crucial | 5-30 minutes |

| Point Collection | Scavenger hunt style; each stop worth different points | Very High – risk vs. reward decisions | Varies |

Some races let you skip checkpoints at a point penalty if you decide the time cost isn’t worth it. This creates interesting strategic decisions—do you ride 3 miles out of your way for 50 points, or skip it and try to finish 10 minutes earlier?

Others disqualify you for missing even one, making every checkpoint mandatory regardless of distance.

The distance varies wildly—some races cover 13-15 miles with 4-5 checkpoints for a casual vibe. Others stretch to 90km (56 miles) with 20+ checkpoints, designed to eliminate all but the most hardcore messengers. Most fall somewhere in the middle at 15-25 miles with 10-15 stops.

What makes this different from real races

Here’s the thing traditional roadies never understand: alley cats aren’t trying to be legitimate cycling events.

As one London racer told Cycling Weekly: “It’s not meant to be illegal, that’s just how it is.” The illegality is baked into the format because you’re racing through active city traffic during regular hours. You can’t get a permit to race through active intersections, so races happen anyway.

Traditional USAC Criterium

- Permits & Insurance – Required, road closures, police presence

- Entry Fee – $30-50+

- Race Numbers – Pinned to jersey

- Categories – Age groups, skill levels, licenses

- Prizes – Cash/points for top finishers

- Course – Closed loop, marked, marshaled

- Atmosphere – Serious, competitive

Alley Cat Race

- No Permits – Unsanctioned, you’re on your own

- Entry – $0-5

- Spoke Cards – Wedged in wheel spokes

- Categories – Maybe gender/bike type, usually just “show up”

- Prizes – Random schwag, DFL gets something too

- Course – The entire city, figure it out yourself

- Atmosphere – Party with racing mixed in

That last point matters. The emphasis on participation over pure competition separates alley cats from traditional racing culture. Many events give special prizes to DFL finishers—anything from training wheels to six-packs of beer to actual respect from the community.

The “Dead Fucking Last” award isn’t a joke; it’s recognition that you showed up, suffered through the whole course, and still finished despite being slowest.

Compare that to a USAC criterium where showing up last just means you got dropped. The anti-establishment ethos runs deep here. There’s a reason these races don’t seek sanctioning—the moment you add insurance, permits, and official timing, you lose the underground spirit that makes them unique.

One racer put it perfectly:

“The racing is the public surface to it. Underneath that there’s lots of culture, quite a bit of history. It wouldn’t exist if it was sanctioned.”

The scene: Bars, spoke cards, and stolen bikes

Races typically start in alleys or parks (hence the name) and finish at bars. The after-party with BBQ, drinks, and music is half the point—these are social events wrapped around competition.

The finish line isn’t some inflatable arch with a timing chip; it’s usually a QR code to scan at a dive bar while your friends are already three beers deep.

Instead of race numbers pinned to jerseys, you get spoke cards—originally Tarot cards, now custom-designed cards with race info and your number written in marker. You wedge them between your rear spokes and keep them as souvenirs.

Serious racers’ wheels look like trading card collections, with cards from races spanning years and multiple cities. Some riders never remove them, building up layers until their wheels rattle like a deck of cards in bicycle spokes.

Entry fees run $5 to free. The low barrier is intentional—these aren’t corporate cycling events. Money collected usually covers spoke card printing and maybe contributes to prize pools. Some races are donation-based to support messenger communities or charities.

Compare this to traditional races charging $40-75 for entry, and you understand why the scene attracts a different crowd.

Prize culture: From custom frames to tampons

Prizes come from local sponsors—bike shops, bars, messenger bag companies. You might win:

- Custom messenger bags (most common—though frequent winners complain about having too many)

- Cash ($500-$3,000 at major races; smaller races rarely offer cash)

- Bike parts (cranksets, wheels, tires, custom framesets)

- Shop gift certificates ($25-100 typically)

- Random donated schwag (t-shirts, bottles of scotch, dog chains)

- Absurd prizes (one woman won a box of super plus tampons for first female)

- One Philadelphia race gave 50¢ off every item for life at Tattooed Mom’s restaurant

Best prize ever!

At The Departed race in Boston, someone won a custom GeekHouse frame—that’s a $1,500+ prize for a $5 entry fee. Talk about ROI.

But here’s the reality nobody posts on Instagram: bikes get stolen at these events. You’re locking up in sketchy areas at 2 AM with dozens of nice bikes clustered together. Organizers aren’t running bag check. Smart racers use beater bikes or bring a friend to watch their stuff.

The irony of bike theft at a bike messenger event isn’t lost on anyone.

The legal reality and safety talk

Let’s not pretend this is safe or legal. It’s neither. Understanding the risks is part of informed participation.

The Matt Manger-Lynch death

On February 24, 2008, Matt Manger-Lynch died racing in Chicago’s Tour Da Chicago series after running a red light and colliding with a car. Witnesses confirmed he blew through the intersection at speed.

His death prompted NYC’s famous Monstertrack race (brakeless fixed-gear only) to cancel permanently.

The organizers wrote: “The safety of the racers is compromised… This is not a tenable position for race organizers.” The race had grown from a small crew of NYC messengers to over 100 participants, many without the street skills to handle brakeless racing through Manhattan traffic.

Harsh reality

You’re racing through active traffic with no course support. If you crash, you call your own ambulance. If you get hit by a car, that’s on you. If you die, your family gets nothing from organizers. The waivers are explicit about this.

The legal gray area

In the UK, organized cycle racing requires police authority. In the US, cities occasionally crack down with tickets or arrests, but enforcement is spotty.

After London’s 2023 Great Alleycat race, UK media went ballistic with headlines like “Cyclist thugs endanger public while racing around streets for cash.” The Daily Mail reported a “close-call where a little boy was nearly hit.”

Organizers typically include waivers stating they’re not responsible for anything—injury, death, arrests, whatever. One race waiver states bluntly: “Do not hurt yourself, do not hurt pedestrians, do not hurt cars, do not die, do not make anyone else die.”

The formula is simple: Organizers throw the event. Riders accept all risk. If you break traffic laws, that’s on you.

You’re racing through active traffic. You’ll probably run red lights. You might get hit. Cops might ticket you. Your bike might get stolen. You could crash and break bones. London racer James explained it best:

“You could ban it tomorrow, and people probably still do it. You could erase it. And then in 20 years time, something like that will pop up again.”

Finding and entering your first race

Alley cats spread through word-of-mouth and social media—no official calendar exists because that would require organization these events intentionally avoid.

Check these sources:

- Local bike messenger associations (SF Bike Messenger Association, NYC Bicycle Messenger Association, etc.)

- Fixed gear Facebook groups for your city

- Instagram accounts for your city’s scene (search #alleycatrace + city name)

- Bike shops with messenger/fixed gear focus

- Ask around at track stands during your daily commute

Most races require nothing but showing up. Some have online registration to manage numbers (especially post-COVID). Registration usually opens 1-2 weeks before the event and fills up fast for popular races.

What to bring:

- Manifest/map bag (waterproof ziplock-style—your manifest will get sweaty)

- Multiple markers or pens (at least 2, preferably 3—they get lost or dry out mid-race)

- Water bottles (races can last 2+ hours; bring more than you think you need)

- Cash ($20-40 for emergencies, bar tab, or bus fare if your bike breaks)

- Phone with maps (or actual paper city map if you’re old school/battery dies)

- Bike lights if riding at night (most races start at dusk or later)

- Basic tools (multi-tool, spare tube, pump—no support if you flat)

Distances range from 10-30 miles with 10+ checkpoints. The fastest riders finish in under an hour by taking optimal routes and hammering between stops. Casual riders might take two hours or more, stopping for beers at checkpoints.

One Toronto race stretched to 90km with 20 checkpoints—designed explicitly to eliminate all but the best messengers.

First-timer warning

Don’t show up on your first alley cat if you’re still sketchy about riding in city traffic. These races assume you already have urban riding skills. You need to be comfortable navigating intersections, riding one-handed while checking a map, and making split-second route decisions.

Why people are obsessed with alley cats

The format is objectively more dangerous and less organized than any sanctioned race. So why do it?

“It’s almost just pure culture. It’s an inevitable sport because people do that stuff for their jobs.”

The chaos and unpredictability aren’t bugs—they’re features. Traditional races tell you exactly where to go, when to turn, how far to the finish. Alley cats give you addresses and say “figure it out.” That problem-solving element while physically redlining creates an experience road racing can’t replicate.

The community aspect matters more than competition for most participants.

You’re not trying to get a USAC upgrade or qualify for nationals. You’re racing against friends to a bar where everyone hangs out afterward comparing routes and talking shit. The inclusivity—DFL prizes, mixed bike types, no categories—means beginners and veterans race the same course.

Alley cats exist outside the cycling industry’s corporate structure and likely always will—that’s the entire appeal.

And there’s the anti-establishment appeal. No corporate sponsors (usually), no entry fees padding someone’s pocket, no sanctioning body rules. Just riders organizing a race for riders because they want to. The DIY ethos permeates everything from hand-drawn spoke cards to checkpoint challenges dreamed up by organizers who know the scene.

Fun fact

Alleycat videographer Lucas Brunelle pioneered first-person POV filming of races in the 2000s, sharing footage that made the chaos look simultaneously terrifying and addictive. YouTube currently hosts 1,000+ alleycat videos, most uploaded since 2006, spreading the culture globally.

Famous races worth knowing

While local underground races dominate most cities, certain events have achieved legendary status in the alleycat world:

- Monstertrack (NYC, cancelled 2008) – Brakeless fixed-gear only, conceived by messenger “Snake” in 2000

- Quake City Rumble (San Francisco, July 4 weekend) – One of the longest-running races, thrown by SF Bike Messenger Association since the early 2000s

- Citywide (Philadelphia) – Started 2020, grew from 20 to 68 riders, filling void left by discontinued Rocky race

- 4/20: Hip to be Square (NYC) – Themed race held on April 20th with obvious cultural references

- Global Warming Alleycat – Simultaneously held in Toronto, San Francisco, Mexico City, Berlin, and NYC on the same day

- Allston Rat Race (Boston, August) – Annual event through Allston neighborhood

These races often attract out-of-town riders traveling specifically to participate, with prizes for “first out-of-towner.” The Citywide race in 2023 drew riders from NYC, DC, Baltimore, and Lancaster—all traveling to Philadelphia for a $5 race that ends at a bar.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

No, most races allow any bike type. Fixed gear bikes dominate because of messenger culture and the bikes’ maneuverability in traffic, but you’ll see everything from mountain bikes to road bikes to cargo bikes. Some specific races (like the defunct Monstertrack) were fixed-only, but that’s rare. The Toronto race founder John Englar actually started races before he was even a messenger, and participants rode whatever they had. Just show up on whatever you’ve got—though understand that fixed gear bikes do offer advantages for quick stops and accelerations in urban environments.

They exist in a legal gray area. The races themselves aren’t explicitly illegal, but racing through traffic, running red lights, and riding recklessly are illegal individual choices. Cities occasionally crack down with tickets or arrests. Organizers put legal responsibility entirely on individual riders—you’re choosing to break traffic laws, not them. UK law specifically requires police permission for organized road racing, making alleycats definitively illegal there. In the US, it varies by city and how aggressive enforcement is at any given time.

Entry fees typically run $5 or are completely free. The low barrier to entry is intentional—these aren’t corporate cycling events. Money collected usually covers spoke card printing and maybe contributes to prize pools. Some races are donation-based to support messenger communities or charities. Compare this to traditional crits charging $40-75, and you understand the appeal. The $5 races usually have better prizes too, thanks to local sponsors contributing products. One Miami race charged $5 and included BBQ, drinks, and prizes at the after-party—basically a full event for less than a burrito.

You’re on your own—period. There’s no course support, medical staff, or sag wagons. If you crash, call your own ambulance (or tough it out and finish anyway, which some riders do). If you get lost, figure it out or DNF (did not finish). This is why manifests matter—you need enough info to navigate even if your phone dies. The self-reliance is part of the culture and why messengers excel at these events. Some races in 2023 mentioned participants ending up in hospitals, which organizers mentioned matter-of-factly in race reports. The waiver you sign makes it crystal clear that organizers accept zero responsibility for anything that happens to you.

Technically yes, but understand what you’re signing up for. You’re racing through city traffic, potentially at night, probably breaking traffic laws, with zero official support. If you’re comfortable navigating your city by bike and can handle riding aggressively in traffic, go for it. If you’re still sketchy about city riding, build those skills first at lower speeds during daylight. Outside Online’s beginner guide notes that races “at least in Minneapolis, are often open and friendly events to anyone on two wheels”—but that friendliness doesn’t mean the race itself is beginner-friendly. Nobody will judge you for showing up slow, but they will judge you for being unsafe and endangering others. Start with shorter races (under 15 miles, fewer checkpoints) to learn the format.

Rarely, and when you do, it’s usually at major established races. Most prizes are bags, bike parts, shop gift certificates, or random donated items. High-profile races occasionally have cash prizes—one Toronto race offered $3,000 CAD for first place, but that’s exceptional. A Boston messenger told Bike Forums about races offering $500 cash prizes, but these are outliers. The norm is practical schwag: messenger bags (most common, though frequent winners complain about having too many), bike components, t-shirts, and six-packs. Prize categories often include DFL (Dead Fucking Last), first fixed gear, first out-of-towner, and various demographic categories. The real prize is street cred, the after-party, and adding another spoke card to your collection.

Final thoughts

Alley cat races aren’t for everyone, and that’s precisely the point. They exist outside the cycling industry’s corporate structure—no entry fees going to insurance companies, no USAC memberships required, no lycra-clad roadies taking themselves too seriously.

The format simulates messenger work because it was created by messengers (well, stoned teenagers first, then messengers adopted it).

The illegal nature isn’t a bug; it’s a feature. The emphasis on community over competition, the after-party at a dive bar, the spoke card collecting, the DFL prizes—all of it reinforces an anti-establishment culture that traditional cycling scenes can’t replicate. These races exist outside sanctioning and likely always will—that’s the entire appeal.

If you’re curious, find your local scene and show up. Worst case, you’ll get lost, arrive DFL, and win a six-pack of cheap beer.

Best case, you’ll discover why people have been doing this since 1989 despite the chaos, the danger, and the complete lack of official recognition. Either way, you’ll understand why a crumpled manifest and a bar at the finish feel more real than any sanctioned crit ever could. Lock your bike well at the finish—seriously.

Sources and references

- Wikipedia – Alleycat Race

- SLUG Magazine – History of Alleycat Racing (John Englar Interview)

- Cycling Weekly – London Alleycat Racer Interview

- Outside Online – Alleycat Bike Racing for Beginners

- Bike Forums – Best Alleycat Checkpoint Ideas

- Bike Forums – Best Prizes From Alleycat Races

- Tracklocross – A Brief History of Alleycats

- The Trellis Philly – Citywide Alleycat III

- SF Bike Messenger Association – QCR History